Neurophysiology of Avoidant Attachment in Adults and the Capacity for Change

Oct 04, 2025Talysha Reeve

Avoidant attachment, anxious attachment and attachment theory in general, are some of the biggest relationship buzz words circulating on social media at present. Unfortunately, there is a phenomenal amount of misinformation surrounding attachment theory being shared, much of which can be immensely problematic for those working towards understanding and addressing attachment styles.

Today, we're diving into understanding how avoidant attachment can impact brain function, and how this can translate into some of the behaviours we see in those with an avoidant attachment style.

The purpose of these blogs is to help people understand themselves, their body, and their relationships. I will always do my best to explain as much of the complexities in simple, easy-to-understand ways. If you ever have any questions or would like clarity, please get in touch

Introduction to Avoidant Attachment & the Brain

Avoidant attachment in adults is linked to distinct neurophysiological patterns, particularly in brain regions and systems involved in social bonding, stress response, and emotional regulation.

These neural patterns are associated with reduced sensitivity to social reward, heightened physiological stress reactivity, and specific brain activation profiles, which may present challenges but not absolute barriers to change.

In simpler terms, people with avoidant attachment often have brains and bodies that respond differently in relationships, compared to those with a secure attachment style.

They may not feel the same sense of reward or comfort from closeness, and their bodies can react strongly to stress even if they appear calm on the surface. This doesn’t mean change is impossible, but it does help explain why intimacy and vulnerability can feel harder for them.

Brain & Function

Before getting to "high level", let's do a quick breakdown of the relevant brain areas and their function involved in the processes we'll be discussing in this article.

Thalamus

Simple Function: Relays sensory information, decides what to pay attention to.

Involved in: Attention, sensory filtering.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex

Simple Function: Detects emotional pain/conflict.

Involved in: Empathy, self-regulation.

Frontal Cortex

Simple Function: Thinks, plans, regulates impulses.

Involved in: Emotional control, reasoning.

Amygdala

Simple Function: Triggers fear or emotional alarm.

Involved in: Threat detection, survival instincts.

Insula

Simple Function: Feels the body’s internal state (interoception).

Involved in: Emotional awareness, body-mind link.

When we look at the areas of the brain that are altered in insecurely attached individuals and the functions they have, it begins to build a picture of how and why many of us can display somewhat confusing behaviours in response to intimacy and closeness in relationships.

Neurophysiological Mechanisms

Opioid System

When we talk about the “opioid system” here, we’re not talking about drugs like oxycodone, we’re talking about the brain’s natural opioid system.

The brain’s opioid system is part of what makes closeness and connection feel good.

This system releases chemicals (like endorphins) that make us feel soothed, safe, and rewarded when we connect with others. It’s the same system that lights up when you hug someone you love, laugh with friends, or feel comfort after crying.

Lower μ-opioid receptor (MOR) availability in the thalamus, anterior cingulate cortex, frontal cortex, amygdala, and insula is correlated with higher attachment avoidance, suggesting diminished capacity for social reward and bonding (Nummenmaa et al., 2015).

It’s not that avoidant adults don’t want connection, but their brains don’t give them the same soothing “reward signals” as easily.

In avoidant attachment, this system is often less active, so closeness doesn’t always feel as rewarding or comforting. That doesn't mean that it isn't comforting or rewarding, just less so in some avoidant-leaning individuals. Over time, in healthy, safe relationships, this can begin to feel more rewarding, it isn't permanently fixed!

Reward and Threat Circuits

Avoidant individuals show reduced activation in the striatum (reward processing) in response to positive social feedback, indicating blunted sensitivity to social rewards. They may also display lower amygdala activation to negative feedback compared to anxious individuals, reflecting different threat processing (Vrtička et al., 2008; Comte et al., 2024).

In everyday terms, avoidant adults don’t get as much of a “reward boost” from positive feedback or closeness, and their brains also process threats differently. Compared to anxious individuals, they may appear calmer or less reactive to rejection, but this often reflects detachment rather than genuine security.

Stress Reactivity

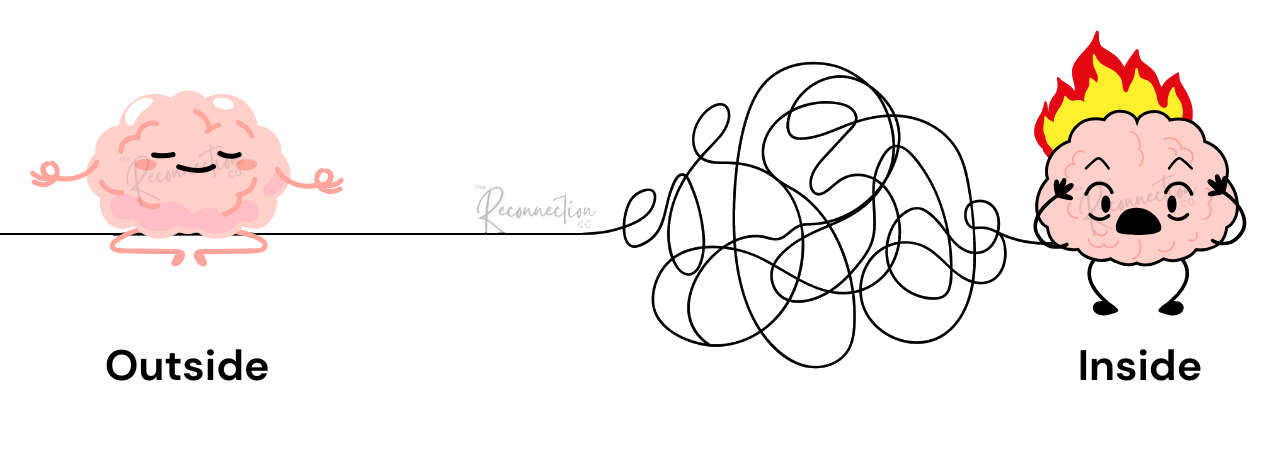

Avoidant attachment is associated with heightened hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and autonomic nervous system reactivity to stress, despite self-reported low distress, indicating physiological vulnerability beneath apparent emotional detachment (Diamond & Fagundes, 2010; Costa-Martins et al., 2016).

This means that even when avoidant people say they’re fine under stress, their bodies tell a different story. Their stress systems go into overdrive, showing that the calm, detached exterior often hides a strong physiological response.

On the outside, they may appear calm and detached, but internally, their bodies very much display signs of distress (increased heart and breathing rate, increases in stress hormones, etc.)

Cognitive and Emotional Processing

Avoidant adults require more cognitive resources for social reasoning under ambiguity and show lower sensitivity to others’ preferences, with altered activation in the anterior insula and inferior parietal lobule (Zhang et al., 2018). Event-related potential studies also show avoidance-dominated early neural responses to emotional cues (Dan et al., 2020; Chavis & Kisley, 2012).

In other words, avoidant adults often have to work harder to understand social situations, especially when things are unclear or emotionally complex. They may also be less tuned in to what others want or need, and their brains react more quickly to avoid emotional cues rather than approach them.

Though, it is important to remember, that these responses are learned, and can be changed or re-learned over time.

Stability and Potential for Change

Relative Stability

Attachment styles, including avoidance, are generally stable into adulthood, rooted in early caregiver interactions and internal working models (Zhang et al., 2018).

Put simply, the patterns we learn in childhood often stick with us. If someone grew up with caregivers who weren’t consistently emotionally available, avoidance can become their default way of relating in adulthood.

BUT...

Capacity for Change

Avoidant attachment in adults is underpinned by specific neurophysiological features, reduced social reward sensitivity, heightened stress reactivity, and distinct brain activation patterns. While these patterns are considered relatively stable as we move into adulthood, there is potential for positive change, especially through targeted interventions and new relational experiences.

While neurophysiological patterns are robust, evidence suggests that attachment-related behaviors and mental health outcomes can be influenced by interventions, life experiences, and relationships (Zhang et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2018; Mikulincer, 1998).

The good news is that anxious and avoidant attachment isn’t fixed forever.

The science is still catching up on the details, but there’s a lot of evidence demonstrating that people can move towards more secure ways of relating. Therapy, supportive relationships, and life experiences can shift behaviour and even reshape the brain over time.

To sum up; avoidant attachment is deeply rooted in the brain and body, which can make connection and closeness feel harder. But it’s not set in stone and with the right support and experiences, change is possible.

References

Nummenmaa, L., Manninen, S., Tuominen, L., Hirvonen, J., Kalliokoski, K., Nuutila, P., Jääskeläinen, I., Hari, R., Dunbar, R., & Sams, M. (2015). Adult attachment style is associated with cerebral μ‐opioid receptor availability in humans. Human Brain Mapping, 36. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22866

Diamond, L., & Fagundes, C. (2010). Psychobiological research on attachment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 218 - 225. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509360906 Dan, O., Zreik, G., & Raz, S. (2020). The relationship between individuals with fearful-avoidant adult attachment orientation and early neural responses to emotional content: An event-related potentials (ERPs) study. Neuropsychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000600

Zhang, X., Li, J., Xie, F., Chen, X., Xu, W., & Hudson, N. (2022). The relationship between adult attachment and mental health: A meta-analysis. Journal of personality and social psychology, 123 5, 1089-1137. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000437

Zhang, X., Ran, G., Xu, W., , Y., & Chen, X. (2018). Adult Attachment Affects Neural Response to PreferenceInferring in Ambiguous Scenarios: Evidence From an fMRI Study. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00139

Vrtička, P., Andersson, F., Grandjean, D., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2008). Individual Attachment Style Modulates Human Amygdala and Striatum Activation during Social Appraisal. PLoS ONE, 3. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002868

Costa-Martins, J., Moura-Ramos, M., Cascais, M., Da Silva, C., Costa-Martins, H., Pereira, M., Coelho, R., & Tavares, J. (2016). Adult attachment style and cortisol responses in women in late pregnancy. BMC Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-016-0105-8

Chavis, J., & Kisley, M. (2012). Adult Attachment and Motivated Attention to Social Images: Attachment-Based Differences in Event-Related Brain Potentials to Emotional Images. Journal of research in personality, 46 1, 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRP.2011.12.004

Mikulincer, M. (1998). Adult attachment style and affect regulation: strategic variations in self-appraisals. Journal of personality and social psychology, 75 2, 420-35. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.2.420

Comte, A., Szymanska, M., Monnin, J., Moulin, T., Nezelof, S., Magnin, É., Jardri, R., & Vulliez-Coady, L. (2024). Neural correlates of distress and comfort in individuals with avoidant, anxious and secure attachment style: an fMRI study. Attachment & Human Development, 26, 423 - 445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2024.2384393

Sign-Up for updates from The Reconnection Co.

Be the first to know when new content & resources from The Reconnection Co. are released.

Your information will never be shared with any third parties.